Year ago, I fell

madly in love on an online dating site with a Danish man who wanted to visit the

national parks in the United States. His

plans of driving with me cross country evoked daydreams of making love in

redwood forests, desert caves, and the desolate sands along the Pacific Ocean. There was no doubt we were soulmates sharing a

need for exploring and discovering. He

knew my gypsy heart before I embraced it after years of being a grounded, busy,

divorced mother of two. When we broke up

a couple years later, we had not yet taken a single road trip together: When he visited the States, he never stayed

long enough because he was a busy airline captain in Denmark and had military

commitments in his country. After we parted ways, my dreams of visiting the national

parks became synonymous with heartbreak and lost love.

Last week, I drove

across California, from its northern Redwood tip, where I now live, to its southern

desert one. On roads such as 101 and West

22, which I had feared driving since I moved to the state last year for its

curving, twisting, winding, narrowing, and rising two-lane highways, I got

stopped for speeding by a trooper who let me go for recently moving to the

state, and I easily weaved in and out of pullouts to let faster trucks go by.

For most of my life,

I have lived in the eastern part of the country, with its paved and brightly

lit highways. I did not know that out West the land ruled and that human

populations dwindled or disappeared across the country’s 450 million acres of

forest. It took some time to accept that I now lived between nowhere and

eternity, and that the end of the road was the start of yet another adventure. My drive across California was a year in the

making with practice drives to Klamath, Mendocino, Trinity, on roads that were closer

to home.

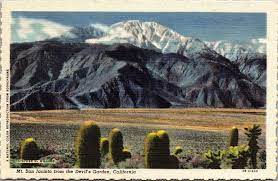

I was now on my

way to Joshua Tree and Channel Islands National Parks, and San Jacinto National

Monument for five days of hiking and sightseeing. On the busier roads of the farmlands in

Southern California, I saw abundant groves of citrus always tended by a solitary

farm worker who seemed to effectively care for miles of fruit trees. Off the

highway, farmland signs reminded Governor Newsom to dam the waters because food

was life. Further south, the humps of emerald greens rolling hills looked like

the backs of giant ancient worms about to break free from the earth to cross

the road. On the five-lane highways around

Los Angeles cars sped as if they were chasing each other. Before reaching the stretched out, intimidating

LA highways, I rose into the mountains of the Angeles National forest, which

made my ears pop and made semis drive so slow they seemed about to stop and park

on highway lanes.

When I reached

Ventura late at night, I saw in the distance shadowy mountain frames and in deep

those same mountains scattered houses dimly lit as if to prove they existed. Fragrances akin to lilac, gardenia, and

honeysuckle wafted in the air, yet these scents were more tart, mysterious, and

not easily detected. To every

destination I drove, I arrived at my hotel at 9:00 p.m., no matter what time I

left my last destination, as if I’d fallen into the rabbit hole of twisting,

bending, California time intended to relax me into its psychic speed of light, contracting

and stretching with epiphanies I had to quickly grasp and let go to be fearlessly

alive in my present moment.

In the past, each

state I’ve lived in had an energetic lesson, like Miami’s demand I live as natural

as its untamed Everglades, even though I hid behind materialistic pursuits and

purchases I could not afford; New York City pounded me with its daily psychic questions:

Who are you? What do you want, REALLY? If I didn’t daily know the answer, my

minutes and hours disappeared between the sounds of wheezing trains, honking cars,

and pounding pedestrian traffic; and Portland, Maine made me choose between

sinking into a Stephen King-like despair and darkness of heartbreak, or soaring

spiritually like seagulls that dominated the skies every day of every season.

In both the East

and Western parts of the country, time felt as if it moved at the speed of

light, yet in the East my time felt rationed and clarified by my

fill-in-the-boxes life, boxes like education, marriage, motherhood that guaranteed

a good life if I navigated my experiences to their successful conclusion. In the West time was just as speedy and

personal but also inclusive of its mythical and tumultuous history with

Natives, settlers, cowboys, Mexicans, hippies, gypsies, hobos, hikers, college

students, Middle-eastern immigrants, and tracts of endless land and oceans always

in my face always, as if stories never died, as if I my daily destiny was

entwined into the whole, as if had to be wild, free, and trusting of it all to

be a part of it all. I was stretched constantly

beyond my comfort zone into the unknown, and it terrified me.

In Humboldt County,

especially, my heart was to be light enough to disappear into the abundance of its

loud-colored flowers; foggy, rainy, and blazing sunny skies, shifting constantly

like scenes in a play; and diverse landscapes demanding a sacred and silent,

“ooh.” If I was to ever claim being and

feeling alive, California was the place to do it, even as I rode on the Redwood

Bus to Eureka--an old Western town as lively today as yesteryear with its western

homes and stories of Jack London, Brett Harte, loggers, and Natives massacred

or imprisoned by White settlers, federal soldiers, or local militia, stories constantly retold as

to not be forgotten--when I sat in the library overlooking Humboldt Bay to

research the history of the place for a children’s book I was writing.

When I reached Scorpion

Island in the Channel Islands National Park after a bumpy ferry ride that made

some passengers seasick and hold up to their faces small plastic bags kindly

handed out by the crew, I took pictures of bright yellow flowers that smelled of

honey and Scrub-jays that posed as if modeling. A middle-aged woman, wearing a traditional abalone

shell necklace with all the blues of the ocean of her Chumash ancestors, was on

the island with friends to do a full moon ritual of peace. She told me about the

fishing ways of her peaceful ancestors who were forcefully removed from their

mountainous island homes and imprisoned and enslaved in Spanish monasteries.

The next day in

Pioneer Town, some miles away from Joshua Tree National Park, I hiked around

the desert with a male guide who knew about the shifts, cracks, and changing

surfaces of desert rocks as if he had spent his past life as a rock. His girlfriend held a sound bath--a meditation

with recorded mantras and spiritual words--in an ancient cave where a monk had

once lived and prayed for months. During the meditation, I sank so deep into my

psyche all I could feel and see were waters from crashing waves, waterfalls,

raging rivers, rains, pressure cleaners wash away my fears of unknown places,

peoples, things… I cried so much lying flat

on the sand my ears filled with tears. My

night ended with a cleansing swim in the pool of my Desert Springs hotel, where

its hot mineral waters sprung deep from the strands of the San Andreas Fault.

The next day I

hiked an elevation of 1000 feet with another guide and two elderly tourists

from the UK. The young guide who walked the mountain once a week, regardless of

whether he was guiding or not, spoke about its wildflowers, like fuschia cactus

blooms, orange red sticky monkey flowers, and blue flowered mountain lilacs,

which fragranced the air. He pointed to the distance where a big-horn ram

gobbled down an entire cactus, including its needles, without any concerns for

passing hikers.

Our guide said the

men of Serrano and Cahuillo people, hunter gather tribes who once lived along

the streams and springs of the mountainous range, rubbed the miniature flowers

of the lavender bush to hide their scents when going on hunts. He also said his hiking poles served as extra

protection from the rattles snakes that lived on the mountain. When he pointed to Bob Hope’s mid-century design

grey monstrosity, I recalled Evangelist church buildings that weekly televised

services of miracles with thousands in attendance. Our guide also mentioned the unbearable

summer heat in the desert valley, once a haven for glamorous movie stars escaping

the pressures of Old Hollywood. He said

the West was still wild, and that it reminded him of the Jetson’s, a 70’s

cartoon show. I agreed even though I was struck by the 20-something man’s

fascination with a cartoon from yesteryear.

My lucky sighting on

the summit was of a woman so earthy, beautiful, and browned by the sun she

seemed risen from the embers of the dirt paths I had just hiked. Mentally, I

crowned her the queen of Palm Springs. She was petite and embraced her

imperfections with nonchalance, especially her crepey, lined, flaccid face and body

exposed in purple jogging shorts and sleeveless white tee for all to see. Her hair was held up under a baseball cap in a

youthful ponytail. None of the social,

cultural demands of beauty and aging hampered her happy stride. Her smile

blazed like the sun and her eyes beamed a joy so ageless and profound she had

to share it with everyone. My trip was now perfect.

I drove back home

the next day and OM’d my way through the sacred Redwood Forest as I drove into Humboldt

County

No comments:

Post a Comment